How to Design Cities for People: An Update

Meredith Glaser revisits questions from “How to Design Cities for People”

A few weeks back we heard from SLO-raised but Amsterdam-based urban strategy and sustainable mobility consultant Meredith Glaser on How to Design Cities for People.

Meredith Glaser & Bike SLO County Executive Director Dan Rivoire at Bello Mundo Cafe

She works on a freelance basis with Dutch municipalities, on international projects with Copenhagenize Design Co, and as a guest researcher/lecturer at the University of Amsterdam. She curates and leads study tours for city leaders around the world. And with any spare time she blogs for Amsterdam Cycle Chic.

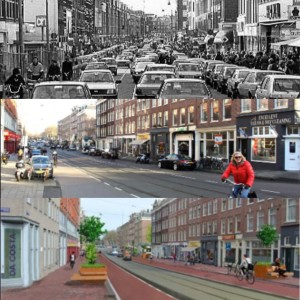

Her talk focused on three key ideas for more people-centered urban planning. First, we need to observe how people are currently using our streets and public spaces. Observing human behavior can provide valuable data for leveraging change. Second, providing choices for people makes them happy. Transportation and land use decisions that result in easily accessible services that are walkable and bikeable can change the way people move in and use their city. Finally, we need to hone and nourish our very human skill of imagining better streets that caterer more to people and places rather than cars and traffic.

Kinkerstraat, Amsterdam. From top: 1981 via www.studiokoning.com; 2016 via @fietsprofessor; near future via City of Amsterdam

We had a packed house at Bella Mundo and after her talk many people asked some great (and tough) questions. Meredith took some time to write up more detailed responses to some of those tough questions.

What zoning changes would you prioritize if you were a SLO planner or policy maker?

I’m not a California zoning code expert, but in true cycling cities, like those in the Netherlands and Denmark, daily needs services are within close distances from where people live and work, and the zoning code is flexible enough to allow for uses to change and adapt with the changing needs of a neighborhood. Mixed use developments with grocery stores, pharmacies, child care and schools, doctors, and other specialty retail strategically placed on the ground level and concentrated on corner sites should be prioritized. Downtown SLO neighborhoods would greatly benefit from a full-service grocery store (or a couple) to support the daily needs of its immediately local residents. (The lot across from Bank of America would be an ideal location for a mixed use development with underground parking, ground floor services, and apartments above. Reminds me of several relatively new developments in Berkeley on University Avenue.) Downtown has ample space for infill and small scale, mixed use developments. Outside of downtown is a whole other issue. New housing developments (out off Broad for example) lack accessibility to services within walking or biking distance, which only perpetuates auto dominated lifestyles. New developments should be clustered near existing services; if they aren’t, then the developers need to provide logical and safe bicycle and walking connections to existing services, schools and other daily amenities. You can read a lot more about these kinds of examples in my new book The City at Eye Level, download it for free here.

Would you agree with the statement that we need to make driving more difficult?

Right now our streets are set up in a way to benefit only one type of user – those driving cars.

We’ve become very accustomed to the conveniences of an unbalanced transportation system that doesn’t reflect the actual costs on society – subsidized gasoline, wide streets, free or very cheap parking, and a ‘door-to-door’ righteous mentality. Modernizing our city streets means allocating some of that space to other users of the road. Best practice bicycle infrastructure that is safe and comfortable and gets people where they need to go has proved an effective way to calm traffic and ease congestion. (Imagine if those bicyclists were in cars!) Surveys from drivers in cities that have created more balanced streets showed that they appreciated the bicycle infrastructure: the infrastructure made the street easier to navigate because each user better understood their place, their role and how they should behave. So it’s not about making it more difficult to drive – it’s not a zero sum game – it’s about balancing out a very unbalanced system.

If we can’t have bike infrastructure, what’s the next best thing?

Best practice bicycle infrastructure has been around for decades; it’s not new and we know how to do it. And compared to car infrastructure, it is low cost, low maintenance and benefits outweigh the risks. The next best thing to permanent bicycle infrastructure is temporary bicycle infrastructure – a trend that is already sweeping the nation. Pilot, pop-up, and demonstration projects are a great way to try out low-stress bicycle infrastructure. Plastic posts or planter boxes can create temporary protected bike lanes or sidewalk extensions. There no reason San Luis Obispo cannot try out some of the ideas that are already out there – no need to reinvent the wheel, especially with that budget surplus we heard about!

I’m not a planner or engineer; what’s my take away from this? What can I do?

Re-establishing the bicycle as a mainstream mode of transport means getting people just like you more involved. If you’re already using the bicycle as a daily transport mode, you are already doing a lot. Keep riding and keep smiling. Tell your friends to join you. Tell your colleagues to join. Have your company buy bikes to leave at the office so they bike to meetings instead of drive. You can advocate for better infrastructure and bicycle facilities by writing to the city council and showing up for city council meetings. Write letters to the Tribune. Join Bike SLO County.

How would you Copenhagenize our downtown streets?

Downtown streets were planned for cars and traffic; it’s time to give more space to people and places. There is ample space to play with and plenty of ideas already out there – just pick a couple and see what works. It’s not rocket science.

If you want more of an answer than that… The design of the streets downtown, for the most part, does not match the uses. Let’s take Higuera: three wide lanes of traffic plus parking on both sides.

This layout is not congruent with the ‘Main Street’ atmosphere, the high amount of pedestrians, and lends to a poor shopping experience. The sidewalks are so narrow people are forced to shuffle around each other. The trees provide a cozy ambiance but the parked cars benefit more from their shade than people. And the traffic is as noisy and distracting as those hideous blinking crosswalk signs. Plenty of bicyclists use the street but it’s unclear where they should ride or park their bicycles. This street (and many others) would majorly benefit from sidewalk widening on both sides, giving people more space to walk and linger – plus restaurants could place more seating outside where people can people watch and enjoy the full sun of that street. Parklets can provide a temporary solution for bike parking or restaurant tables or just more space for people to sit. Raised bike ways (or at least 6′ bike lanes with buffers for car doors) on both sides could allow for increased accessibility to shops as well as through movement while remaining low-stress, comfortable, and intuitive for all users. Again, there are great bones here and lots of space to play with!

How do you convince engineers? Or rather, why are engineers in the Netherlands already “doing it right”?

For 7,000 years streets were designed for people and by people. 100 years ago that all changed and our streets were engineered for the first time in human history. It appears as though engineers aren’t going away any time soon, so it might be time to inject some real life and real design into the engineering curriculum. In the Netherlands where cycling is an every day, mainstream form of transportation, engineers are also bicycling so they experience their work on a daily basis. That’s not the case in other cities and towns, especially in the U.S. It might be very difficult for an American engineer to imagine (and design, no less) bicycle infrastructure if he or she has never experienced best practice infrastructure first hand. I think that’s why study tours are so important. Feeling and experiencing comfortable, safe bicycle infrastructure that’s been around for a century – plus talking to the experts themselves – is better than any PowerPoint presentation.

If you’re interested in study tours check out the Copenhagenize Master Class or contact Meredith for a custom study tour in the Netherlands.

Do you think Cal Poly should play a role?

Absolutely. University decision makers need to make bicycles and mass transit clear priorities, but again linking these networks and nodes seamlessly with housing, daily needs and services, and connections to the downtown core. Bicycle parking should be ample, obvious, and intuitively placed. Policies also must limit students from bringing cars into SLO – but that has to be combined with land use decisions that provide for the daily needs of students.

Cal Poly is not the only stakeholder though. In addition to transitional city officials, key decision makers from local hospitals, SLO school district, developers, Old Mission Church and schools, major employers, and the Chamber of Commerce need to get on board. As I said last Wednesday, this isn’t about getting more bicycles on the streets of San Luis Obispo, it’s about giving people more choices for how they get around. It’s about balancing out our streets and giving more space to people. And it’s about building a better, happier, more livable town for the children growing up here.

Meredith Glaser is an urban strategy and mobility consultant. She is originally from San Luis Obispo, holds Masters degrees in urban planning and public health from UC Berkeley, and has been based in the Netherlands since 2010. Meredith holds a guest appointment at the University of Amsterdam, where she co-leads a summer program on urban cycling and conducts research on cross-national policy transfer and knowledge exchange related to mobility. She hosts other university-level student groups and international professional delegations for cycling and mobility study tours. Meredith also directs the Amsterdam office for Copenhagenize Design Co., which advises cities and towns around the world regarding bicycle urbanism, reestablishing the bicycle as transport in cities, policy, planning, communications and general urban design. In her spare time she blogs for Amsterdam Cycle Chic. She lives in Amsterdam with her husband, daughter, 4 bikes and no car.